In all aspects of our lives, time is precious. It is one of the few things we can never get back and have a limited amount of. In primary school in Florida, teachers have to cover a lot of mathematics content in a year (FLDOE, 2022a). In my experience, there’s often even less time to plan for instruction, grow professionally, collaborate, and complete managerial tasks. It goes without saying, that teachers probably want to use their limited time wisely.

My approach in teaching for the last few years has been to ask myself, “what purpose does this serve me and/or my students?”. Ideally, we want more tasks and activities that benefit students’ academic achievement—isn’t that why education exists?

Florida has proudly announced this year that they are the first state to move to progress monitoring students rather than standardized tests (FLDOE, 2022). The state claims this approach has numerous benefits, one being those smaller check-ins throughout the year can allow instruction to be adjusted and increasingly meet students’ needs (FLDOE, 2022).

Around here, we’re all about data-driven instruction and meeting students’ individual needs. However, I have to ask myself, is what Florida is proposing truly progress monitoring? According to (Stecker et al., 2008), progress monitoring provides teachers with data to alert them of a student’s lack of adequate progress. Numerous progress monitoring assessments are out there. Florida chose an adaptive test that gives students questions based on their answers to previous questions. Progress monitoring has positively affected education (Safer & Fleischman, 2005). However, as may be expected, progress monitoring only leads to benefits if the teacher uses the progress monitoring data to adjust instruction (Ysseldyke & Bolt, 2007). My question about progress monitoring systems such as the one Florida has recently adopted or its previous system, i-Ready, concerns how teachers use the data in mathematics.

The Florida progress monitoring assessment results show teachers how each student performs within the different reporting categories, such as fractional reasoning. Based on their website, the reports don’t show how students performed on individual standards, average responses, or individual answers (FLDOE, 2022b), which would be highly beneficial to teachers. It makes me wonder why we withhold this valuable information from teachers and if that’s what’s best for kids.

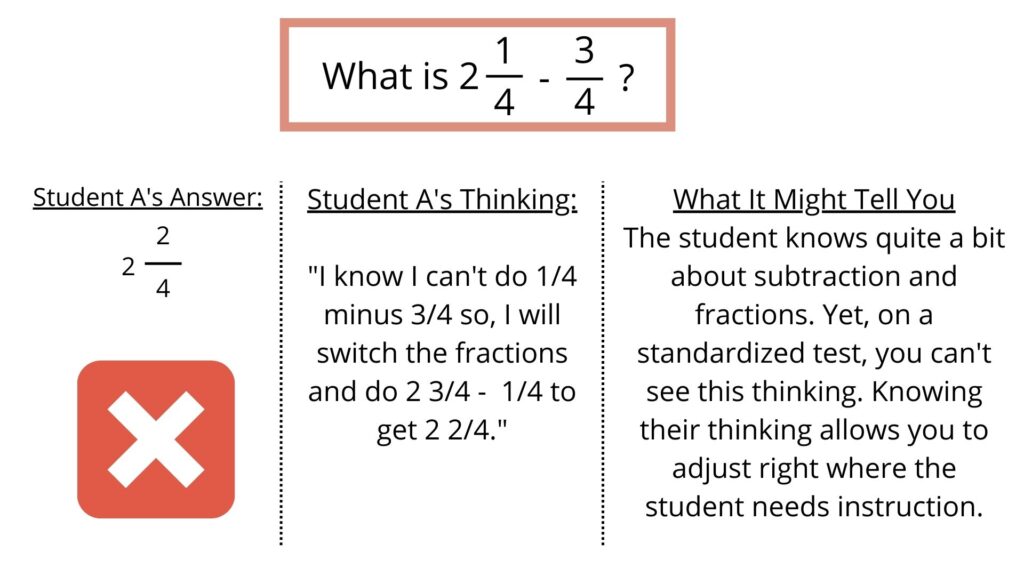

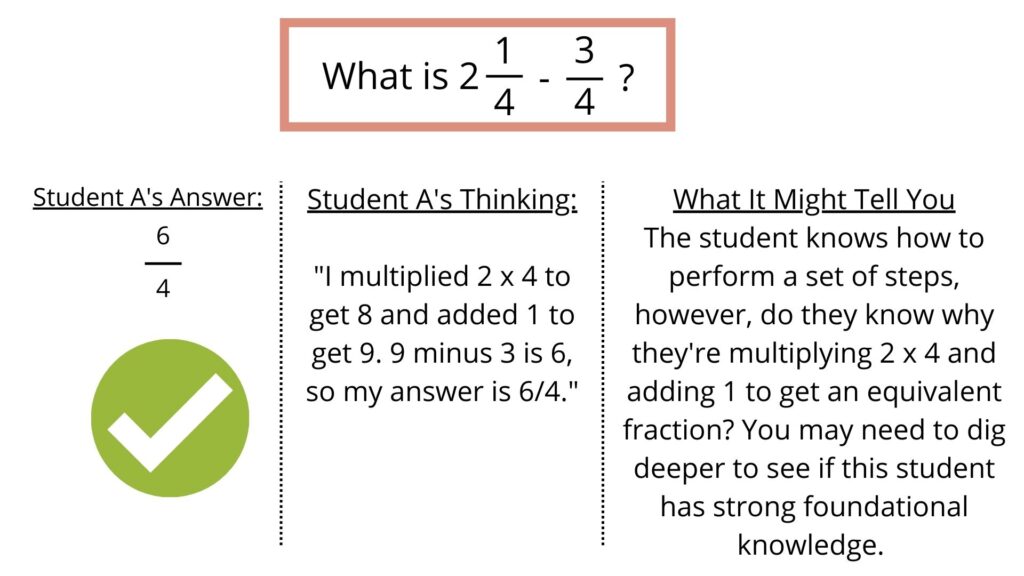

This overview of the new Florida system makes me wonder if this way of monitoring student progress is only partly helpful for teachers to plan instruction. Knowing the amount of content fourth-grade students learn about fractions, a report telling me a student earned a 65% mastery in fractions tells me little about how I should teach them. From my perspective, a report which tells me that one student scored a 0% while another scored a 100% can be equally unhelpful. Pure scores on an assessment can lead us to misconceive what a student knows or doesn’t know. Take the following two examples: one student answered correctly and another incorrectly. We might miss what students know or don’t know by only knowing if they got the right answer.

I am an advocate of progress monitoring. However, I wonder if teachers may have to supplement Florida’s assessment system with their progress monitoring in between the state tests to use data to guide instruction successfully. Progress monitoring, such as concrete-representational-abstract assessments, error pattern analysis, and student interviews (Assad, 2015), can allow teachers to understand more about student understanding (Lembke et al., 2012). These assessments take time; however, as discussed at the start of this blog post, time is valuable. Teachers may benefit from discussing with their instructional coaches, teammates, administrators, and district support personnel what additional progress monitoring assessment can be helpful in truly understanding how to adjust instruction.

Teaching is incredibly complex. Each teacher holds beliefs, knowledge, and experiences that guide their teaching. Students also bring their perspectives and experiences, which adds to the complexity. I believe including teachers in the conversation about how this benchmark data can be used in schools to help them and aim to positively affect student achievement is critical to the new system’s success. Without teachers being included in the narrative, we fail to understand a critical part of teaching.

Resources

Assad, D. A. (2015). Task-based interviews in mathematics: Understanding student strategies and representations through problem solving. International Journal of Education and Social Science, 2(1), 17-26.

Lembke, E. S., Hampton, D., & Beyers, S. J. (2012). Response to intervention in mathematics: Critical elements. Psychology in the Schools, 49(3), 257-272. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21596

Florida Department of Education (2022a) BEST Standards. K-12 BEST Standards. Retrieved from: fldoe.org/academics/standards/subject-ara/math-science/mathematics

Florida Department of Education (2022b). FAST Progress Monitoring Assessment Manual. FAST: Florida Assessment of Student Thinking. Retrieved from: flfast.org.

Safer, N., & Fleischman, S. (2005). Research matters: How student progress monitoring improves instruction. Educational Leadership, 62(5), 81-83.

Ysseldyke, J., & Bolt, D. M. (2007). Effect of Technology-Enhanced Continuous Progress Monitoring on Math Achievement. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 453-467. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087933